Spotting the difference between fraud and progress

I have recommended Matt Levine's writing before, but his recent article in Bloomberg is so good it asks for a tribute, a share and an explanation.

It questions the core of what makes economics a science of progress: are revenue and financial transactions actually a good predictor of success?

How to measure progress

To answer this question, let's first look at what has historically been the most reliable way to measure progress in the world. Right, to increase economic growth. Most other measures of welfare are correlated with it. And once people start caring about new issues (like climate change), those will also be supported by a growing GDP. [1]

On a smaller scale, similar logic applies. When an investor wants to see whether a company is making progress, revenue growth is one of the most important and easiest predictors the investor will ask about.

However, GDP and revenue measurements only make sense when they measure real economic activity (financial transactions) between different competing entities. The typical example being: a buyer and a seller in a marketplace.

How to fake progress

Now, let's circle back to Matt Levine's article. He describes two different ways in which people can fake their economic activity:

(1) investors subsidize early revenue growth. The financial capital might help you to sell your products at a discount to your customers.

(2) you can fake early revenue growth, a practice also known as wash trading. A recent report from Chainalysis indicates enormous potential wash trading activity.

The first is an acceptable business practice, the second is illegal, but both result in business activity seeming more exciting than it is, and both allow you to fool future investors and users about how succesful the activity is. And although in scenario (1) at least you can show to the world that people go through the trouble of using your product, if I literally get offered a free meal or free money, I may just go through the trouble to get it. In the most extreme case where the activity never even cares about making "real" revenue, you can call it a ponzi scheme.

Now, what if we could go a step further and combine the two practices? What if you can make your users investors, giving all of them an incentive to both subsidize the platform and to commit wash trading. As the practice becomes distributed to your entire userbase, it may become completely indistinguishable from "real" economic activity.

The scariest thing about this phenomenon is economist Dror Poleg and Matt Levine's conclusion:

"“A Ponzi. But it makes sense. It will be the dominant marketing method of the next decade and beyond.” I don’t like it! But I am not confident that he’s wrong."

How to save progress

The problem with Ponzi schemes is that although they may not be real economic activity, they may certainly be profitable. There are several ways in which the negative ponzi-like impact which the user-is-investor paradigm has can be softened:

- Make investments less liquid. When a user/investor knows that they are in it for the long run, they may be less inclined to incur costs in the short run when it is unclear when a payout can be expected.

- Increase transaction costs for parties which trade a lot between them. There may be cryptographic proofs which allow parties to (privately) prove that they have not interacted with each other before - though I'm not sure that solution is feasible given the existence of mixers.

- Establish systems to identify wash trading. If this was hard to identify in the old world, it is more difficult now. When your entire userbase is a potential investor incentivised to use your system with others at a loss, good luck identifying what is "real" economic activity and what is wash activity. One thing which might be possible is to measure people's stake in a particular protocol - though similar to wealth taxation - people will always try to find ways to hide their assets.

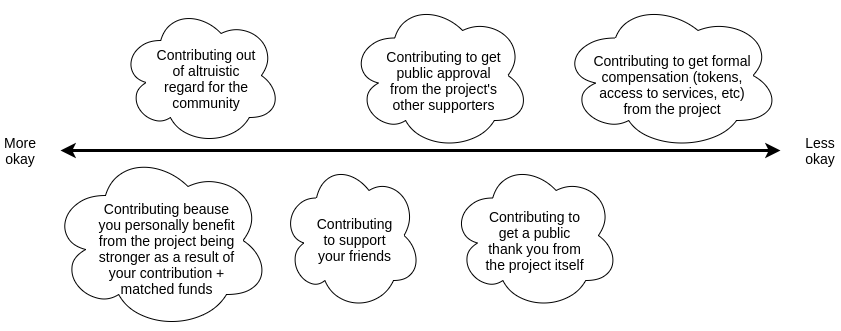

Whether two parties are different economic entities is not a binary concept but a spectrum. For example, in the image below there are different ways in which a donation may or may not be an accurate signal for progress, and this means that even if we established trader's identity it might not give us enough information whether the trade is legitimate or not:

Or perhaps we let real economic activity fight back twice as hard, and give people more ownership in assets which have proven themselves to be productive.

[1] One issue which it does not measure clearly is inequality, which we can measure through orthogonal approaches like evaluating the income/wealth ratio between the lowest and highest earning groups, or a mix like the nash product (economic growth x inequality).